I like to divide execution loops into two main categories: Synchronous loops and Asynchronous loops. The first one does its tasks based on some sort of clock (or clocks) at a fixed sampling period (or periods). The second type performs its tasks based on events that are triggered by other parts of the program, or by external devices integrated into the program. If you’re using your mouse wheel to scroll down this web page, the wheel motion is an asynchronous event triggered by the mouse device that notifies the main application that something happened and that the wheel position data will be sent. The main application uses that data and then takes care of moving the page up.

Moving forward, let’s focus on synchronous execution loops. The most general code layout contains a group of tasks that are performed before the program starts the execution loop, the loop itself, and tasks that are performed after the loop finishes running. If DAQ devices are being used for instance, a typical task before starting the loop is to look for (and do some checks on) the DAQ device and then connect to it. After the loop finishes, properly disconnecting from the DAQ device is a typical task done at that time. Other tasks, such as loading and saving data, starting and stopping other processes or interfaces, also fall into the before and after categories.

The simplest possible code (shown below) only contains the execution loop and would run forever until the power is cut off or someone hits “CTRL” + “C” on the keyboard. While this is sometimes all that’s needed, I prefer to add some sort of exit condition.

import time

import datetime

# Doing tasks before entry condition

print('Running forever ...')

print('Interrupt or press "CTRL"+"C" to stop.')

# Running execution loop

while True:

# Doing computations

for i in range(100000):

pass

# Doing I/O tasks

print('I/O at', datetime.datetime.now().time())

# Pausing for 1 second

time.sleep(1)

Running forever ...

Interrupt or press "CTRL"+"C" to stop.

I/O at 20:22:26.737740

I/O at 20:22:27.740305

I/O at 20:22:28.743494

I/O at 20:22:29.745530

I/O at 20:22:30.747698

I/O at 20:22:31.749704

I/O at 20:22:32.752015

I/O at 20:22:33.755986

I/O at 20:22:34.758986

I/O at 20:22:35.760987

I/O at 20:22:36.763165

I/O at 20:22:37.765439

I/O at 20:22:38.770925

You should first notice that on the output above on the right, the time step is slightly over 1 second. In this case, the longer the computations take, the farther away this number will be from 1 second. While you could account for the computational time and subtract it from the sleep duration, even the corrected value tends to drift over time, loosing it’s accuracy. Let’s improve that and add an exit condition by using a clock, as shown below. It could represent for how long a test needs to run. If the code is part of a GUI (Graphical User Interface), the entry and exit conditions could be just a start and a stop buttons.

import time

import datetime

import numpy as np

# Assigning time parameters

tsample = 1 # Data sampling period (s)

tstop = 100 # Test stop time (s)

# Initializing timers and starting main clock

tprev = 0 # Previous time step

tcurr = 0 # Current time step

tstart = time.time()

# Doing tasks before entry condition

print('Running for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

# Running execution loop

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Updating previous time and getting current time (s)

tprev = tcurr

tcurr = time.time() - tstart

# Doing computations

for i in range(100000):

pass

# Doing I/O tasks every `tsample` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tsample) - np.floor(tprev/tsample)) == 1:

print(

'I/O at', datetime.datetime.now().time(),

'(Elapsed time = {:0.3f} s)'.format(tcurr))

# Doing tasks after exit condition

print('Done.')

Running for 100 seconds ...

I/O at 20:27:43.673925 (Elapsed time = 1.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:44.671919 (Elapsed time = 2.000 s)

I/O at 20:27:45.675318 (Elapsed time = 3.002 s)

I/O at 20:27:46.675509 (Elapsed time = 4.003 s)

I/O at 20:27:47.674825 (Elapsed time = 5.002 s)

I/O at 20:27:48.673115 (Elapsed time = 6.000 s)

I/O at 20:27:49.673116 (Elapsed time = 7.000 s)

I/O at 20:27:50.674293 (Elapsed time = 8.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:51.675247 (Elapsed time = 9.002 s)

I/O at 20:27:52.674257 (Elapsed time = 10.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:53.675288 (Elapsed time = 11.002 s)

I/O at 20:27:54.674371 (Elapsed time = 12.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:55.673409 (Elapsed time = 13.000 s)

I/O at 20:27:56.675287 (Elapsed time = 14.002 s)

I/O at 20:27:57.674133 (Elapsed time = 15.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:58.674246 (Elapsed time = 16.001 s)

I/O at 20:27:59.673134 (Elapsed time = 17.000 s)

I/O at 20:28:00.675795 (Elapsed time = 18.003 s)

I/O at 20:28:01.674195 (Elapsed time = 19.001 s)

I/O at 20:28:02.674295 (Elapsed time = 20.001 s)

I/O at 20:28:03.675202 (Elapsed time = 21.002 s)

...

I/O at 20:29:19.674898 (Elapsed time = 97.002 s)

I/O at 20:29:20.674071 (Elapsed time = 98.001 s)

I/O at 20:29:21.672220 (Elapsed time = 99.000 s)

I/O at 20:29:22.675361 (Elapsed time = 100.003 s)

Done.

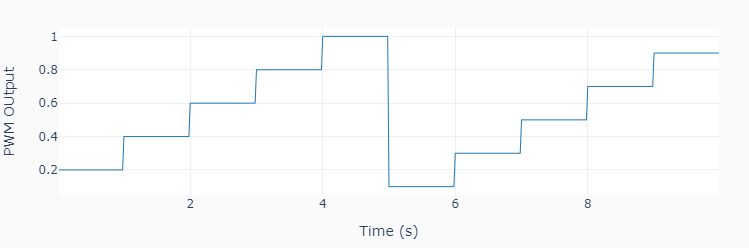

Observe that after adding the sampling clock condition, the elapsed time between steps is consistently 1 second (within a couple of milliseconds, as shown above on the right). Even if you were to run the code for an indefinite amount of time, the sampling period would stay consistent. As shown in the next piece of code, it is possible to add multiple clock conditions to the execution loop. For instance, one clock for data acquisition and one clock for data display.

import time

import datetime

import numpy as np

# Assigning time parameters

tsample = 0.2 # Data sampling period (s)

tdisp = 1 # Data display period (s)

tstop = 100 # Test stop time (s)

# Initializing timers and starting main clock

tprev = 0 # Previous time step

tcurr = 0 # Current time step

tstart = time.time()

# Doing tasks before entry condition

print('Running for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

# Running execution loop

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Updating previous time and getting current time (s)

tprev = tcurr

tcurr = time.time() - tstart

# Doing computations

for i in range(100000):

pass

# Doing I/O tasks every `tsample` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tsample) - np.floor(tprev/tsample)) == 1:

print(

'I/O at', datetime.datetime.now().time(),

'(Elapsed time = {:0.3f} s)'.format(tcurr))

# Displaying data every `tdisp` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tdisp) - np.floor(tprev/tdisp)) == 1:

print(

'Displaying data',

'(Elapsed time = {:0.3f} s)'.format(tcurr))

# Doing tasks after exit condition

print('Done.')

Running for 100 seconds ...

I/O at 10:18:01.743822 (Elapsed time = 0.201 s)

I/O at 10:18:01.944788 (Elapsed time = 0.402 s)

I/O at 10:18:02.144784 (Elapsed time = 0.603 s)

I/O at 10:18:02.347786 (Elapsed time = 0.803 s)

I/O at 10:18:02.545785 (Elapsed time = 1.002 s)

Displaying data (Elapsed time = 1.002 s)

I/O at 10:18:02.743788 (Elapsed time = 1.200 s)

I/O at 10:18:02.944790 (Elapsed time = 1.402 s)

I/O at 10:18:03.143787 (Elapsed time = 1.600 s)

I/O at 10:18:03.343785 (Elapsed time = 1.801 s)

I/O at 10:18:03.542788 (Elapsed time = 2.000 s)

Displaying data (Elapsed time = 2.000 s)

I/O at 10:18:03.742835 (Elapsed time = 2.200 s)

I/O at 10:18:03.943834 (Elapsed time = 2.402 s)

I/O at 10:18:04.144792 (Elapsed time = 2.602 s)

I/O at 10:18:04.343825 (Elapsed time = 2.801 s)

I/O at 10:18:04.542789 (Elapsed time = 3.000 s)

Displaying data (Elapsed time = 3.000 s)

I/O at 10:18:04.742791 (Elapsed time = 3.201 s)

I/O at 10:18:04.943792 (Elapsed time = 3.401 s)

I/O at 10:18:05.146791 (Elapsed time = 3.602 s)

I/O at 10:18:05.347791 (Elapsed time = 3.803 s)

I/O at 10:18:05.542792 (Elapsed time = 4.000 s)

Displaying data (Elapsed time = 4.000 s)

I/O at 10:18:05.745793 (Elapsed time = 4.203 s)

I/O at 10:18:05.945793 (Elapsed time = 4.402 s)

I/O at 10:18:06.142790 (Elapsed time = 4.600 s)

...

I/O at 10:19:41.143165 (Elapsed time = 99.600 s)

I/O at 10:19:41.342204 (Elapsed time = 99.800 s)

I/O at 10:19:41.544215 (Elapsed time = 100.001 s)

Displaying data (Elapsed time = 100.001 s)

Done.

Finally, depending on what you’re trying to do and how the code is laid out, CPU usage could become significant. Always keep an eye out for that. On a Windows platform, you could use the Task Manager.