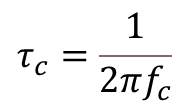

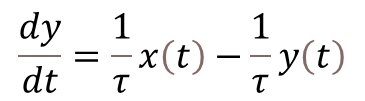

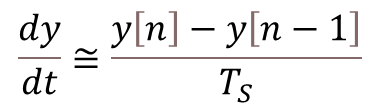

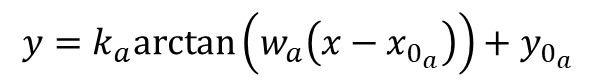

The inverse tangent (arctangent) and tangent functions are quite helpful when it comes to fitting data that characterize the response of some types of sensors. Sensors that transition between two saturation states can have their transfer function (relationship between input and output) represented by the arctangent. The tangent function, on the other hand, comes into play when we need to fit the inverse of the sensor transfer function, with the purpose of linearizing its output in the control software.

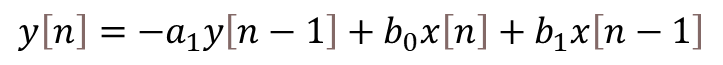

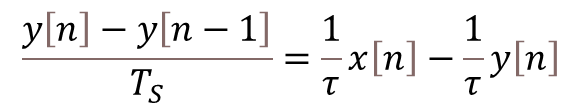

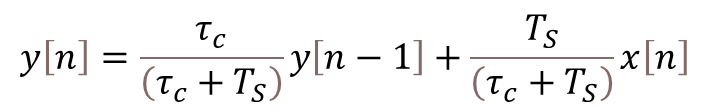

Let’s use the Python SciPy package for optimization and root finding, more specifically, the curve_fit function. which is well suited for the case where nonlinear coefficients need to be determined. Convenient forms for data fitting of arctangent and tangent are shown below:

The coefficients![]() that produce the best data fit in a least squares sense can be determined using

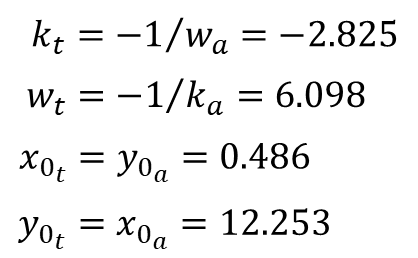

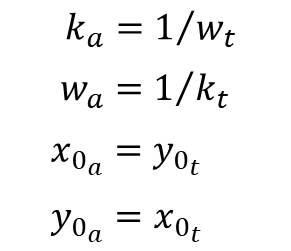

that produce the best data fit in a least squares sense can be determined using curve_fit. It should be noted that, if you invert the tangent function above, it’s fairly easy to arrive at:

While the fitting problem using the arctangent and tangent functions can be treated completely independently, in some cases, one function does a better job fitting the data than the other one. The coefficient relationships above can be used to go from tangent to arctangent (or vice-versa), when the inverse of the desired function produces a better fit to the (inverted) data than the desired function itself.

Arctangent Function Fit

The following Python code fits data from a photocell sensor as described in Line Tracking Sensor for Raspberry Pi. xdata in the code represents the sensor position in mm, while ydata represents the photocell normalized voltage output.

# Importing modules and classes

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

# Defining function to generate Matplotlib figure with axes

def make_fig():

#

# Creating figure

fig = plt.figure(

figsize=(5, 4.2),

facecolor='#ffffff',

tight_layout=True)

# Adding and configuring axes

ax = fig.add_subplot(

facecolor='#ffffff',

)

ax.grid(

linestyle=':',

)

# Returning axes handle

return ax

# Defining parametrized arctangent function

def f(x, k, w, x0, y0):

return k * np.arctan(w*(x-x0)) + y0

# Defining data points

xdata = [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16]

ydata = [0.432, 0.448, 0.477, 0.547, 0.653, 0.800, 0.908, 0.933, 0.955]

# Estimating initial parameter values

p0 = [1, 1]

p0.append(0.5*(max(xdata)+min(xdata)))

p0.append(0.5*(max(ydata)+min(ydata)))

# Fitting data

output = curve_fit(f, xdata, ydata, p0=p0, full_output=True)

# Extracting relevant information from output

copt = output[0]

res = output[2]['fvec']

numeval = output[2]['nfev']

msg = output[3]

# Plotting data and fitted function

xi = np.linspace(min(xdata), max(xdata), 100)

yi = f(xi, *copt)

ax = make_fig()

ax.set_xlabel('x', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('y', fontsize=12)

ax.scatter(xdata, ydata)

ax.plot(xi, yi, linestyle=':')

# Calculating residual sum of squares (RSS)

rss = np.sum(res**2)

# Calculating root mean squared error (RMSE) from RSS

rmse = np.sqrt(rss/len(ydata))

# Calculating R-square

r2 = 1 - rss/np.sum((ydata-np.mean(ydata))**2)

# Displaying fit info

print('Found solution in {:d} function evaluations.'.format(numeval))

print(msg)

print('R-square = {:1.4f}, RMSE = {:1.4f}'.format(r2, rmse))

print('')

print('Coefficients:')

print(' k = {:1.3f}'.format(copt[0]))

print(' w = {:1.3f}'.format(copt[1]))

print(' x0 = {:1.3f}'.format(copt[2]))

print(' y0 = {:1.3f}'.format(copt[3]))

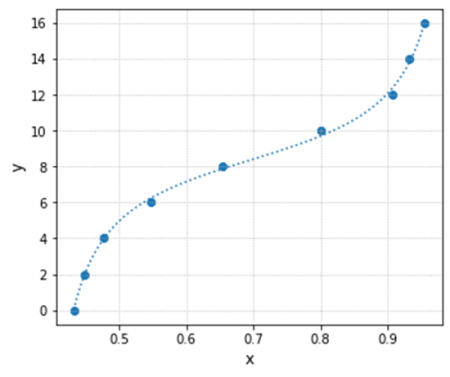

Running the program will generate a plot of the data points with the fitted curve, as well as some statistical information about the fit quality and the optimal coefficients![]() .

.

Found solution in 43 function evaluations.

Both actual and predicted relative reductions

in the sum of squares are at most 0.000000

R-square = 0.9990, RMSE = 0.0065

Coefficients:

k = 0.211

w = 0.377

x0 = 8.565

y0 = 0.701

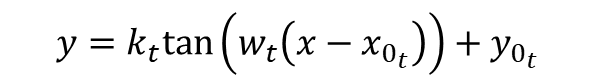

Tangent Function Fit

The same code can be used to fit a tangent function to a data set. All you need to do is replace the arctangent function with the tangent one and have the appropriate xdata and ydata. In this particular case, the previous data set arrays were just swapped. The program output after the modifications is also shown. The full code can be found on my GitHub repository.

# Defining parametrized tangent function

def f(x, k, w, x0, y0):

return k * np.tan(w*(x-x0)) + y0

# Defining data points

xdata = [0.432, 0.448, 0.477, 0.547, 0.653, 0.800, 0.908, 0.933, 0.955]

ydata = [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16]

Found solution in 54 function evaluations.

Both actual and predicted relative reductions

in the sum of squares are at most 0.000000

R-square = 0.9985, RMSE = 0.1998

Coefficients:

k = 2.383

w = 4.896

x0 = 0.696

y0 = 8.377

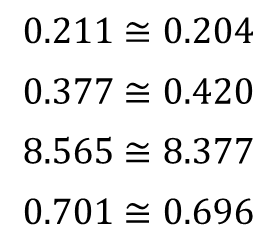

If we compare the coefficients from the arctangent fit with the ones from the tangent fit, using the relationships derived at the top of the post, they don’t quite match. Even when using the exact same data set by swapping xdata and ydata.

This result shouldn’t be a surprise, since the error between y values and their predictions, used inside the fitting algorithm, are not equivalent even with identical swapped data sets. Additionally, the distribution of the data points among the x coordinates also affects the optimal coefficient values of the fitted function.

Going from Arctangent to Tangent

Let’s take a closer look at the influence of the data point distribution on the resulting fitted function, and when we are better off using the coefficients of the function fitted to the inverse data set.

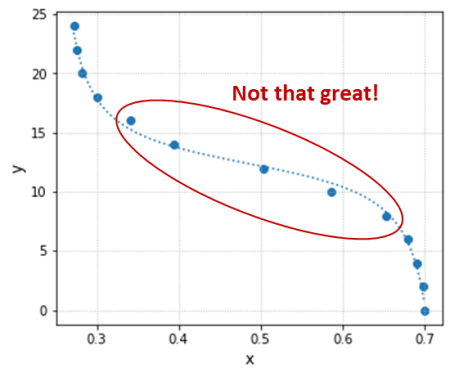

We want to fit a transfer function to the following data using the tangent function:

# Defining parametrized tangent function

def f(x, k, w, x0, y0):

return k * np.tan(w*(x-x0)) + y0

# Defining data points

xdata = [0.700, 0.698, 0.691, 0.680, 0.654, 0.587, 0.504, 0.394, 0.341, 0.300, 0.282, 0.275, 0.272]

ydata = [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24]

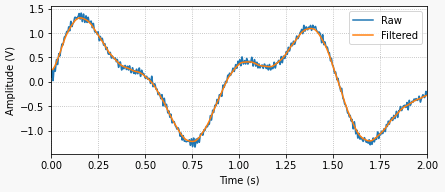

Using the Python program with the code snippet above substituted into it, we get the fit results below. Even though the R-square is a respectable value, the fitted function doesn’t do a good job capturing the transition between the two end states.

Found solution in 80 function evaluations.

Both actual and predicted relative reductions

in the sum of squares are at most 0.000000

R-square = 0.9959, RMSE = 0.4766

Coefficients:

k = -2.143

w = 6.469

x0 = 0.485

y0 = 12.382

Due to the overall shape of the transfer function and the fact that the data was originally collected at constant y increments, there is a high concentration of points along the x axis on both ends of the test data range. That leaves the region of interest (inside the red ellipse) with relatively fewer points, biasing the fitted function towards the low and high x value regions (outside the red ellipse).

One way to tackle this issue is by inverting the data set and using, in this case, the arctangent function:

# Defining parametrized arctangent function

def f(x, k, w, x0, y0):

return k * np.arctan(w*(x-x0)) + y0

# Defining data points

xdata = [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24]

ydata = [0.700, 0.698, 0.691, 0.680, 0.654, 0.587, 0.504, 0.394, 0.341, 0.300, 0.282, 0.275, 0.272]

The new fit is now done with x values that are evenly distributed, removing the bias that occurred when the tangent function was used.

Found solution in 60 function evaluations.

Both actual and predicted relative reductions

in the sum of squares are at most 0.000000

R-square = 0.9992, RMSE = 0.0049

Coefficients:

k = -0.164

w = 0.354

x0 = 12.253

y0 = 0.486

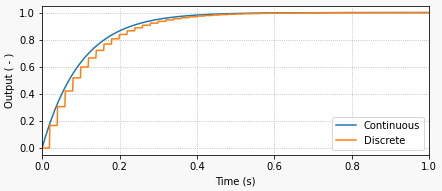

Finally, we can then use the coefficient relationships to go from arctangent, that produces a better overall data fit, to the desired tangent transfer function. The plot below shows the new tangent function in orange (using the arctangent coefficients) in contrast with the original one in blue.