Along the lines of the Motor Speed Control post, let’s reuse some of our Python classes to control the angular position of a DC motor. We’ll also look into how to tune the PID using the Ziegler-Nichols method, as well as different ways to apply a position set point input.

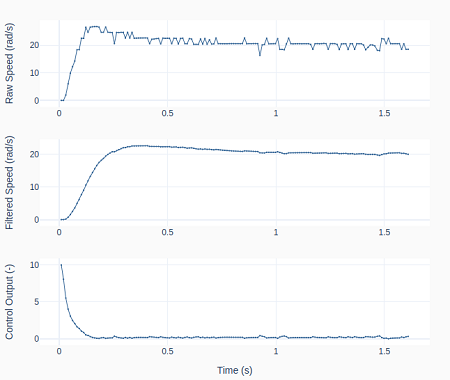

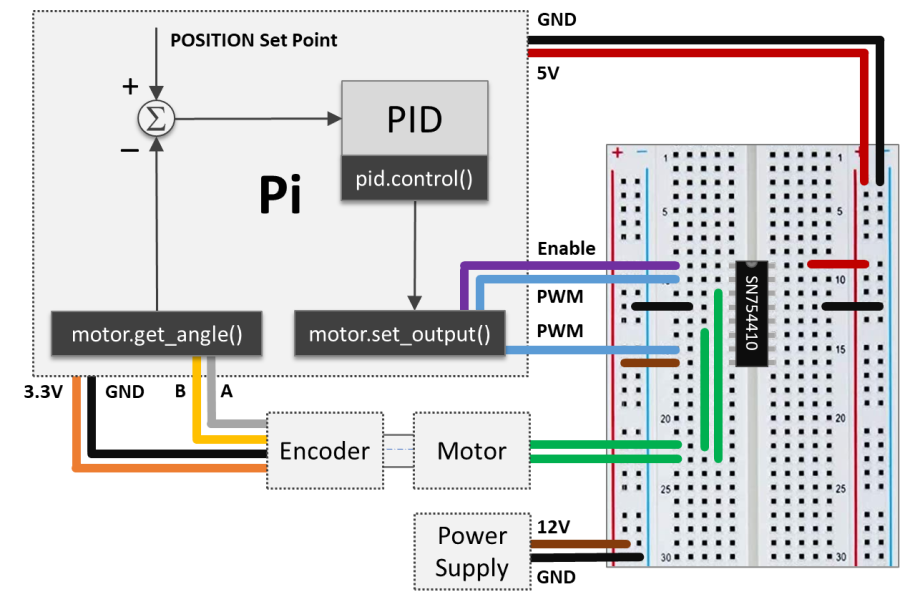

Like before, the starting point is the Raspberry Pi setup that can handle both a PWM output and an encoder input. Unlike the speed control scenario, there’s no need to calculate and filter the speed from the measured angular position.

Most of the work presented in this post was done using the Python code below. It uses the Motor class and the Digital PID class as its building blocks. On my GitHub page, you can find the complete version of this program, a slight variation of it (used for the PID tuning), and all the classes that it uses.

# Importing modules and classes

import time

import numpy as np

from gpiozero_extended import Motor, PID

# Setting general parameters

tstop = 1 # Execution duration (s)

tsample = 0.01 # Sampling period (s)

thetamax = 180 # Motor position amplitude (deg)

# Setting motion parameters

# (Valid options: 'sin', 'cos')

option = 'cos'

if option == 'sin':

T = 2*tstop # Period of sine wave (s)

theta0 = thetamax # Reference angle

elif option == 'cos':

T = tstop # Period of cosine wave (s)

theta0 = 0.5*thetamax # Reference angle

# Creating PID controller object

kp = 0.036

ki = 0.379

kd = 0.0009

taupid = 0.01

pid = PID(tsample, kp, ki, kd, tau=taupid)

# Creating motor object using GPIO pins 16, 17, and 18

# (using SN754410 quadruple half-H driver chip)

# Integrated encoder on GPIO pins 24 and 25.

mymotor = Motor(

enable1=16, pwm1=17, pwm2=18,

encoder1=24, encoder2=25, encoderppr=300.8)

mymotor.reset_angle()

# Initializing variables and starting clock

thetaprev = 0

tprev = 0

tcurr = 0

tstart = time.perf_counter()

# Running execution loop

print('Running code for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Pausing for `tsample` to give CPU time to process encoder signal

time.sleep(tsample)

# Getting current time (s)

tcurr = time.perf_counter() - tstart

# Getting motor shaft angular position

thetacurr = mymotor.get_angle()

# Calculating current set point angle

if option == 'sin':

thetaspcurr = theta0 * np.sin((2*np.pi/T) * tcurr)

elif option == 'cos':

thetaspcurr = theta0 * (1-np.cos((2*np.pi/T) * tcurr))

# Calculating closed-loop output

ucurr = pid.control(thetaspcurr, thetacurr)

# Assigning motor output

mymotor.set_output(ucurr)

# Updating previous values

thetaprev = thetacurr

tprev = tcurr

print('Done.')

# Stopping motor and releasing GPIO pins

mymotor.set_output(0, brake=True)

del mymotor

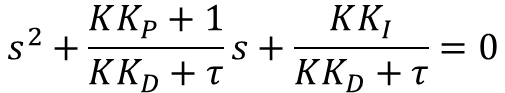

PID Tuning using Ziegler-Nichols

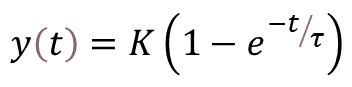

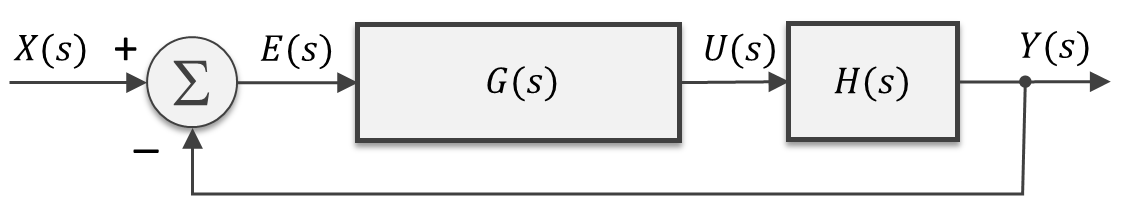

Unfortunately, the PID tuning method presented in the previous post cannot be used to obtain an initial set of controller gains. The first-order approximation used for the speed response doesn’t work for the angular position, since it increases linearly once a steady-state speed is reached. In other words, the DC motor system with position as an output is an integrator of the corresponding system with speed as an output.

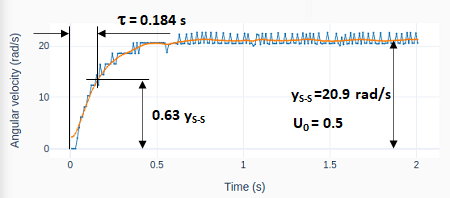

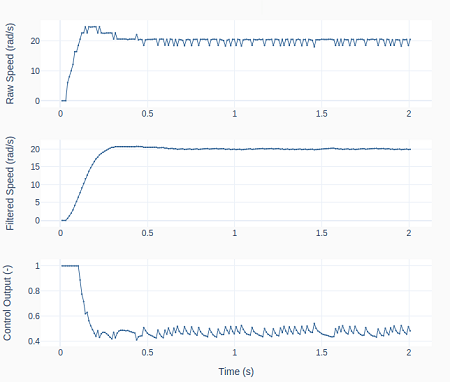

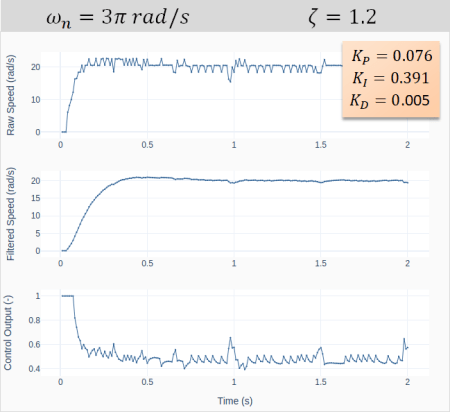

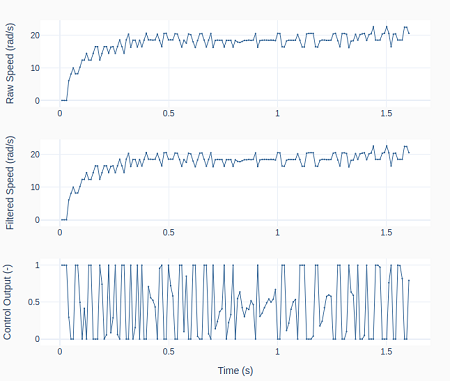

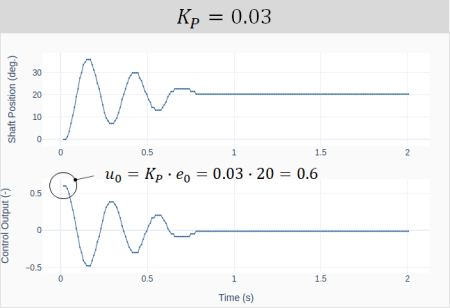

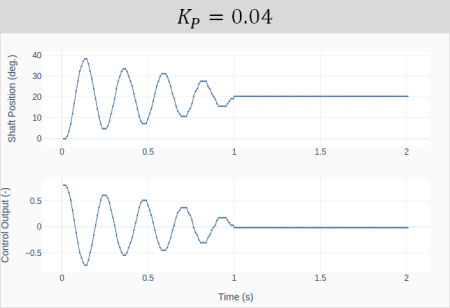

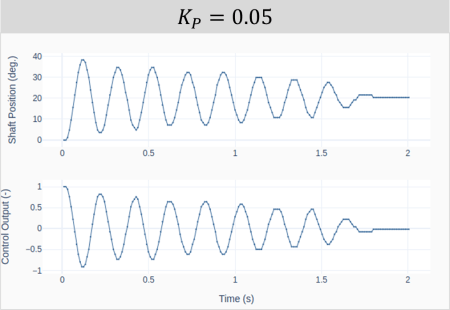

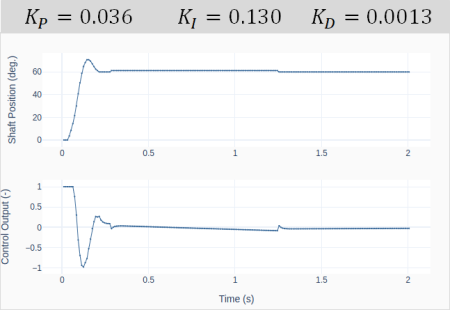

That brings us to the Ziegler-Nichols method, which can be used with a closed-loop system. In our case, the feedback loop is closed on the motor shaft position. The method is based on starting the tuning process only with a proportional gain and then increasing its value, until the closed-loop system becomes marginally stable. I.e., oscillates with a constant amplitude. The four plots below show the response and corresponding controller output for increasing values of![]() .

.

The first question that comes to mind is what should the starting value of![]() be. A good guess is based on the size of the step input and the saturation limit of the controller. The very instant the step input is applied, the position error going into the controller is equal to the step size. Therefore, at that moment, the controller output is given by

be. A good guess is based on the size of the step input and the saturation limit of the controller. The very instant the step input is applied, the position error going into the controller is equal to the step size. Therefore, at that moment, the controller output is given by ![]() . As shown in the first plot, for

. As shown in the first plot, for ![]() , the initial controller output is 0.6 for a step input of 20 degrees. The choice of the step size and the initial proportional gain are such that the controller doesn’t saturate (in our case, 1 is the output limit) and there’s still room to increase the gain without running “too much” into the saturation zone.

, the initial controller output is 0.6 for a step input of 20 degrees. The choice of the step size and the initial proportional gain are such that the controller doesn’t saturate (in our case, 1 is the output limit) and there’s still room to increase the gain without running “too much” into the saturation zone.

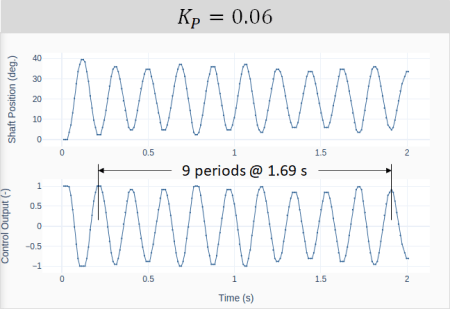

The ultimate proportional gain![]() is achieved when the system oscillates with a constant amplitude. In our example,

is achieved when the system oscillates with a constant amplitude. In our example, ![]() . Under this condition, the ultimate oscillation period

. Under this condition, the ultimate oscillation period![]() can be extracted from the last plot above and is calculated as

can be extracted from the last plot above and is calculated as![]() .

.

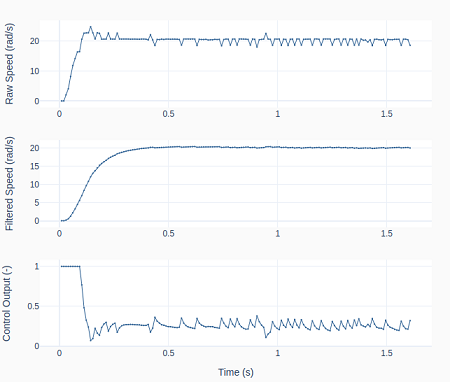

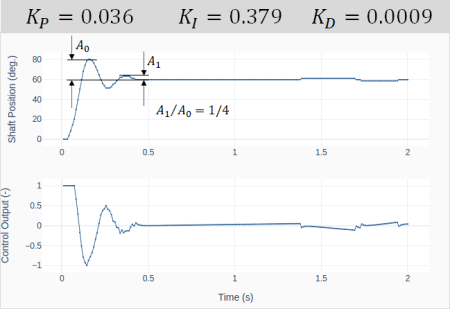

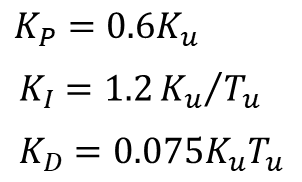

The Ziegler-Nichols method states that for a 1/4 decay ratio of the closed-loop system response, the PID gains are given by:

The graph shows the closed-loop response for a shaft position step input of 60 degrees. The PID gains were obtained after substituting![]() and

and![]() into the formulas above.

into the formulas above.

Observe the 1/4 decay ratio of the amplitude. Also, the fact that the motor position cannot meet exactly 60 degrees causes the integral error to build up, resulting in small position “jumps” around the 1.4 and 1.7 s marks.

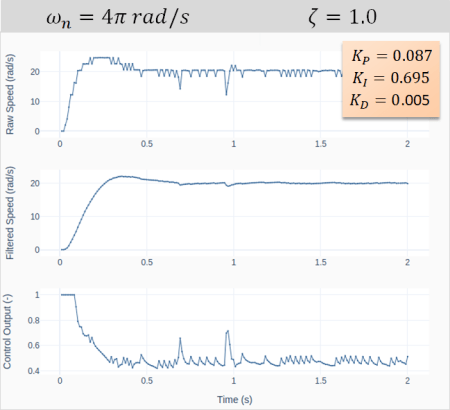

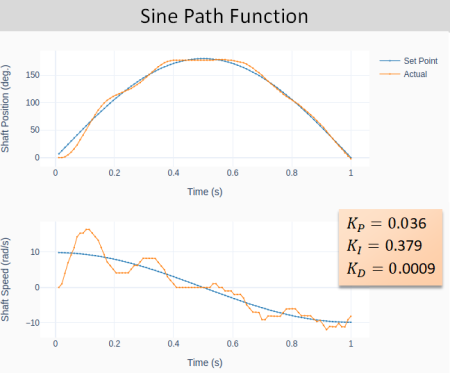

Starting from the gains defined by using the Ziegler-Nichols method, let’s do some manual tuning aiming to decrease the oscillation of the closed-loop response. That can be achieved by decreasing the integral gain and increasing the derivative gain.

The plot on the left shows the system response for values that were obtained after a few attempts. The idea is to later compare the effect of the two sets of gains on the response (when applying different types of position set point inputs).

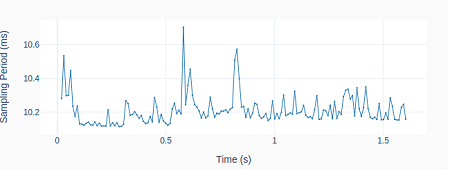

Sine and Cosine Path Functions

While using step changes to move from one position to another is fine, there are situations where we want the position to follow a pre-determined path. By choosing the right combination of PID gains and characteristics of the path function, it’s possible to greatly improve the tracking ability of the position controller.

In this post let’s take a look at two trigonometric functions (sine and cosine), that can be used to move the motor to a given set point angle and then back to its initial position. By inspecting the code above, we can identify the sine and cosine path functions shown below.

and

By choosing suitable values of the amplitude![]() and period

and period![]() , the two functions can produce motion paths that have the same set point (maximum) angle and the same motion duration to return to the original angular position.

, the two functions can produce motion paths that have the same set point (maximum) angle and the same motion duration to return to the original angular position.

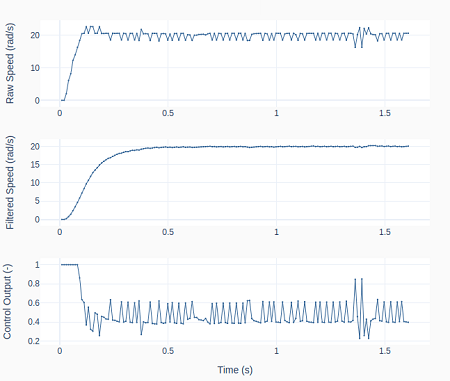

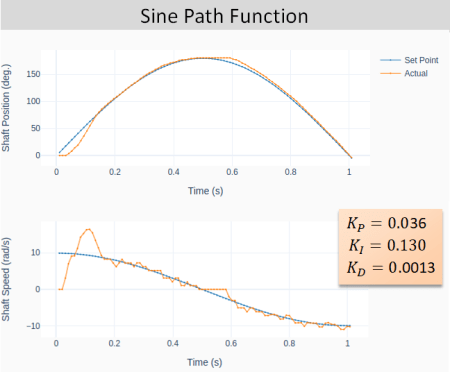

The next two plots show the general closed-loop tracking performance for the sine-based path function, using the two sets of PID gains obtained in the previous section. Notice the more pronounced oscillatory behavior for the more aggressive set of gains. Additionally, due to the nature of the sine-based path, the initial and final speeds are not zero.

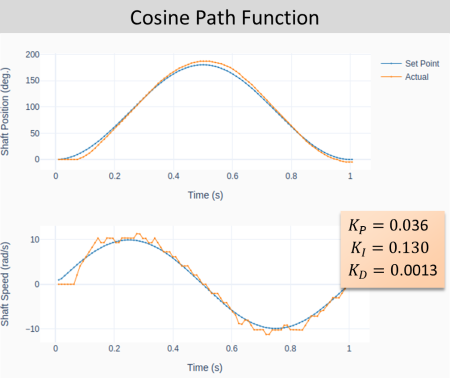

The cosine-based path function on the other hand (shown below) has zero initial and final speeds. That characteristic can greatly reduce the system oscillation, especially at the very beginning of the motion.

Final Remarks

When it comes to position control, the DC motor is usually part of a machine or even a robot, where it is important to understand the dynamic behavior of the complete system. Speed and accuracy are usually conflicting goals that have to be compromised to obtain the best performance of the closed-loop control system. However, having a suitable path function can minimize undesired system oscillation caused by the input excitation (or path).

In future posts we will take a deeper look into path functions, particularly the ones that in addition to having zero end-point speeds also have zero end-point accelerations. Stay tuned!