A circular or ring buffer is a fixed-size data structure that is commonly used in real-time software applications to store a pre-defined number of values. The analogy of a ring with a fixed number of positions is quite useful to capture the FIFO (First-In-First-Out) nature of such data structure. Once the buffer is full, the first element that was written (“In” ) to the buffer is the first one to be overwritten (“Out”) by the next incoming element.

Circular buffers are particularly useful in situations where the data is continuously being sampled and calculations need to be done using a pre-defined sample size or continuous visualization is required.

The two images below represent a circular buffer with 10 positions. On the left, with four elements written to it being 5 the “first in”. On the right, the buffer is full where the value 3 was written. Note how the current write position pointer moves around as new values are added.

Additionally, a ring buffer has basically two states: not-yet- full (left image) and full (right image). The not-yet-full state occurs after the buffer is initialized and exists only until it becomes full. We will see later how this affects the Python code used to represent the buffer.

Once the buffer state changes to full, the FIFO nature of this type of data structure becomes evident. In the next two images, the next element “in” is the value 12, replacing the “first in” value 5, which therefore is the “first out”. The next value “in” is 2, replacing the “second in” value 10, and so on.

In the example figures above, we could imagine the buffer being used to display the average value of its elements (once the buffer reaches the full state). As time progresses, a new sample is written to the buffer, replacing the oldest sample. Each figure of the full buffer is a snapshot at a given time step of the sampling process. In this case the average values are 6.4, 7.1, and 6.3.

Python Implementation

The most elegant way to implement the circular buffer is by using a class. Also, a true circular buffer does not involve shifting its elements to implement the FIFO structure. The current position pointer is used to keep track of where the newest element is.

The circular buffer class should have the following attributes:

bufsize: the number of elements that the circular buffer can hold (integer)data: the list of elements, i.e., the buffer itselfcurrpos: the current position pointer (integer)

The class should also have two methods:

add(): writes an element to the bufferget(): returns a list containing the buffer elements

Let’s go over some of the features of the Python implementation below:

- As mentioned earlier, the ring buffer has two states (not-yet-full and full). The first state only exists for a limited time until the buffer is filled up. With that in mind, it makes sense to define the

__Fullclass within theRingBufferclass with the exact same methods. Once the buffer is full, the original class is permanently changed to the full class implementation, with itsadd()andget()methods now superseding the original ones. - The not-yet-full

add()method just does a regular list append operation of new elements to the buffer list. It is also in this method that the class is changed to the__Fullclass once the buffer reaches its capacity. - The full

add()method, on the other hand, writes the new element at the current (newest) element position and increments the current position by one unit (wrapping it around, or resetting it, once the buffer size value is reached). - More interesting however is the full

get()method. It splits thedatalist at the current position into two lists which are then concatenated. The list going fromcurrposto the last element goes first, then comes the list from the first element tocurrpos(excluded). By returning this concatenated list, the method fully implements the circular buffer without shifting any of it elements! Inspect thedataattribute as you add elements to a full buffer to see what the original list looks like.

class RingBuffer:

""" Class that implements a not-yet-full buffer. """

def __init__(self, bufsize):

self.bufsize = bufsize

self.data = []

class __Full:

""" Class that implements a full buffer. """

def add(self, x):

""" Add an element overwriting the oldest one. """

self.data[self.currpos] = x

self.currpos = (self.currpos+1) % self.bufsize

def get(self):

""" Return list of elements in correct order. """

return self.data[self.currpos:]+self.data[:self.currpos]

def add(self,x):

""" Add an element at the end of the buffer"""

self.data.append(x)

if len(self.data) == self.bufsize:

# Initializing current position attribute

self.currpos = 0

# Permanently change self's class from not-yet-full to full

self.__class__ = self.__Full

def get(self):

""" Return a list of elements from the oldest to the newest. """

return self.data

# Sample usage to recreate example figure values

import numpy as np

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Creating ring buffer

x = RingBuffer(10)

# Adding first 4 elements

x.add(5); x.add(10); x.add(4); x.add(7)

# Displaying class info and buffer data

print(x.__class__, x.get())

# Creating fictitious sampling data list

data = [1, 11, 6, 8, 9, 3, 12, 2]

# Adding elements until buffer is full

for value in data[:6]:

x.add(value)

# Displaying class info and buffer data

print(x.__class__, x.get())

# Adding data simulating a data acquisition scenario

print('')

print('Mean value = {:0.1f} | '.format(np.mean(x.get())), x.get())

for value in data[6:]:

x.add(value)

print('Mean value = {:0.1f} | '.format(np.mean(x.get())), x.get())

The output shown next is produced if the code containing the class is executed. The values and the states of the ring buffer shown in the figures at the beginning of the post are recreated in an iterative process that simulates some data acquisition. Note how the ring buffer class changes once the buffer is full.

<class '__main__.RingBuffer'> [5, 10, 4, 7]

<class '__main__.RingBuffer.__Full'> [5, 10, 4, 7, 1, 11, 6, 8, 9, 3]

Mean value = 6.4 | [5, 10, 4, 7, 1, 11, 6, 8, 9, 3]

Mean value = 7.1 | [10, 4, 7, 1, 11, 6, 8, 9, 3, 12]

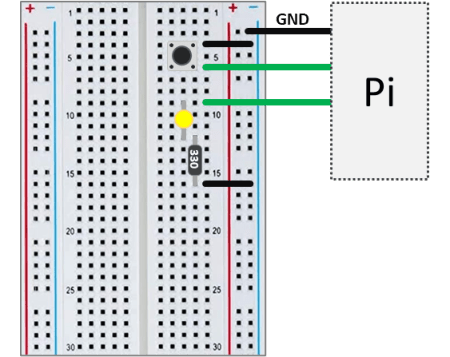

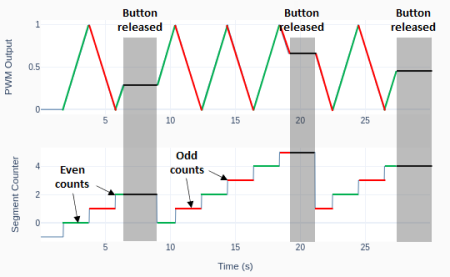

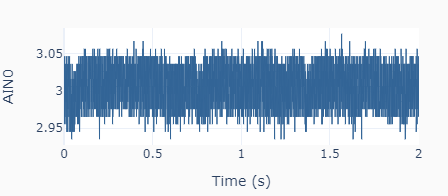

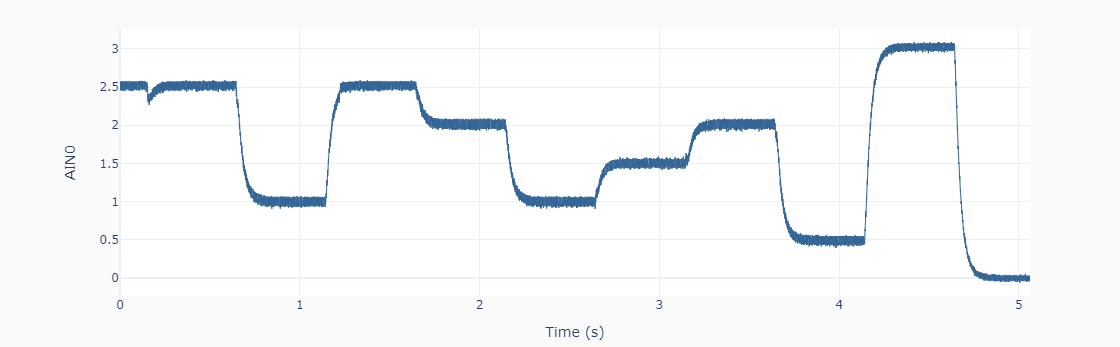

Mean value = 6.3 | [4, 7, 1, 11, 6, 8, 9, 3, 12, 2]As a final remark, in the Pulse Rate Monitor post, the buffer that was used is not a true circular buffer, since the elements in the arrays are shifted by one position for every new value being sampled. Because the buffer is relatively small (200 elements) and the sampling period of the data is reasonably large (0.1s) this solution does not constitute a problem. You can check out the code that implements a true ring buffer for the monitor on my GitHub page.