Closed-Loop PID (Proportional Integral Derivative) controllers are quite popular when it comes to regulating a dynamic system that has to follow a desired set point. When compared to other types of controllers, it has the advantage of requiring little to no knowledge about the system plant for it to be designed successfully.

Before we start, the idea of this post isn’t to go over the theory of control systems. The goal is to talk about some of the characteristics of a PID controller and how to go about implementing a discrete (or digital) one with some additional features to make it more robust. In the end, we will have a Python class that represents a PID, which can be used in an execution loop to control a process or a dynamic system.

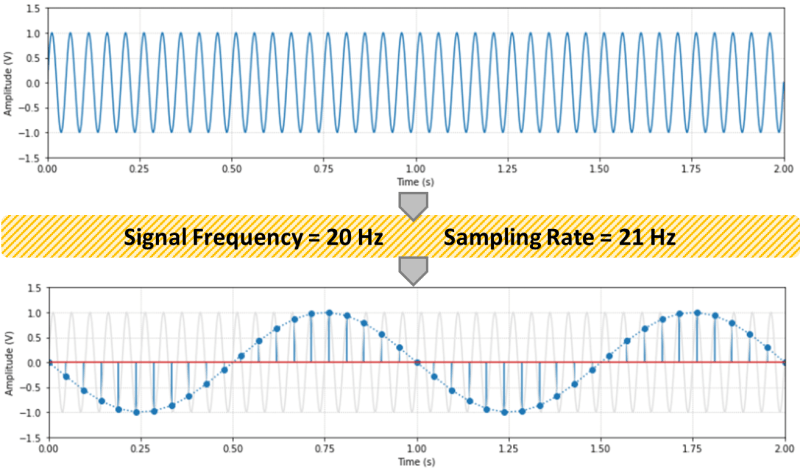

The diagram below illustrates a closed-loop system, where all the signals are represented in the time domain. The three terms of the PID are shown separately, where the controller output value![]() is the sum of the individual term contributions. The regulation of the plant output

is the sum of the individual term contributions. The regulation of the plant output![]() to the desired set point value

to the desired set point value![]() is achieved as the controller continuously brings the error

is achieved as the controller continuously brings the error![]() between the set point and the plant output to zero.

between the set point and the plant output to zero.

The PID gains![]() ,

,![]() and

and![]() can be tuned so that the closed-loop dynamic behavior of

can be tuned so that the closed-loop dynamic behavior of![]() meets the desired response requirements. In broad terms, the proportional term reacts directly to the current value of the error between set point and desired output. Usually, the proportional term by itself cannot bring the error to zero (since it relies on the existence of an error to produce a controller output). That’s where the integral term comes into the picture: because it takes into account the accumulated error (or the integrated error) it will compensate the smallest deviations. Over time the accumulation of the deviation will be large enough to cause a controller output. The proportional and integral terms combined can bring the error to zero (for a steady state input) for most dynamic systems.

meets the desired response requirements. In broad terms, the proportional term reacts directly to the current value of the error between set point and desired output. Usually, the proportional term by itself cannot bring the error to zero (since it relies on the existence of an error to produce a controller output). That’s where the integral term comes into the picture: because it takes into account the accumulated error (or the integrated error) it will compensate the smallest deviations. Over time the accumulation of the deviation will be large enough to cause a controller output. The proportional and integral terms combined can bring the error to zero (for a steady state input) for most dynamic systems.

The derivative term reacts to the rate of change of the error and can be effective for sudden set point changes, by helping reduce the response overshoot. In practical applications, using a derivative term can be tricky due to its sensitivity to noise that’s typically present in the measurement of the plant output.

As a side note, the plots throughout this post were generated using MATLAB and Simulink, where the corresponding m-files and Simulink model can be found on my GitHub page. I should emphasize that I did spend some time exploring and trying to use the Python Control Systems package. However, nothing can beat Simulink when it comes to quickly representing and simulating dynamic systems. Especially when non-linearities are being modelled. Spending $100 on that MATLAB student license might be something to think about.

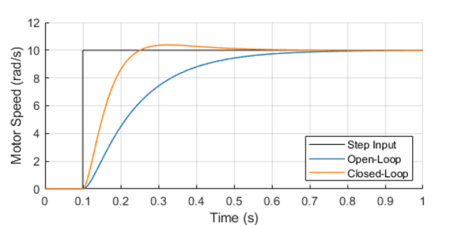

One way to analyze the performance of a control system (in our case a PID controller) is by measuring the closed-loop system’s response to a step change of the set point.

Because in future posts we will be doing closed loop control of small low-budget DC motors, let’s use as a plant a somewhat fictitious motor with an integral gear box. The plot shows the closed-loop system response in contrast with the open-loop response.

The controller output (armature voltage), as well as the individual contribution of each of the PID terms, is also shown. Observe how the proportional and derivative terms go to zero as the response approaches its steady-state value, leaving the integral term in charge of keeping the error![]() at zero.

at zero.

It’s important to mention that both the open-loop as well as the closed-loop responses end up at the same final armature voltage of 2.8 V.

For our DC motor model, the armature voltage required to produce a motor speed output of 10 rad/s without any external load is 2.8 V. In the case of the open-loop system, I use that knowledge to apply a step input of 2.8 V to the motor. On the other hand, the step input to the closed-loop system is in fact the desired speed output of 10 rad/s. The PID controller will apply whatever armature voltage is needed to follow the speed set point, even when the manufacturing variability of the motor or other sources of error are present. That’s the first takeaway that most people working with control systems are very familiar with. The second point I want to make is that the improved response time, compared to the open-loop system, can only be achieved because the controller has an excess output capability (up to 12 V in our motor model) that can be tapped into at the moment of the step change.

Without getting into stability margins, the closed-loop system can be just as fast as you want. The issue at hand becomes how much do you want to “oversize” your system so it can obtain that stellar dynamic response. Understanding you engineering requirements is key when choosing the right hardware “size” for the desired closed-loop system behavior.

Discrete PID Implementation

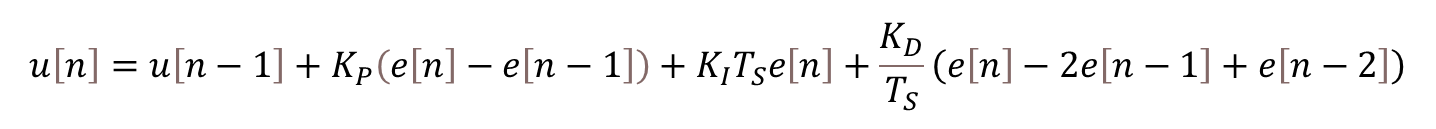

The most basic digital PID implementation can be obtained from taking the derivative of the controller output equation

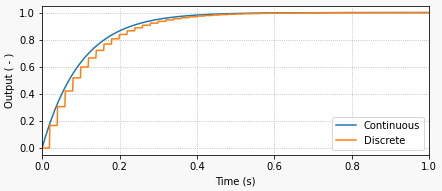

and using backward difference (with sampling period![]() ) to approximate the derivatives. The difference equation below can be obtained by following the steps shown here.

) to approximate the derivatives. The difference equation below can be obtained by following the steps shown here.

This implementation has two notable advantages:

- Because the previous output value

is taken into account for the output calculation, the controller can be seamlessly started from an open-loop condition by assigning the current open-loop output value to the very first

is taken into account for the output calculation, the controller can be seamlessly started from an open-loop condition by assigning the current open-loop output value to the very first  .

. - The PID gains

,

, and

and obtained from the design of a continuous controller are still valid in its discrete representation (provided a fast enough sampling period

obtained from the design of a continuous controller are still valid in its discrete representation (provided a fast enough sampling period is used).

is used).

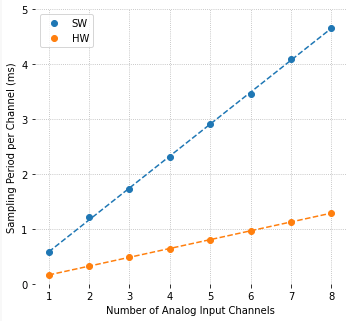

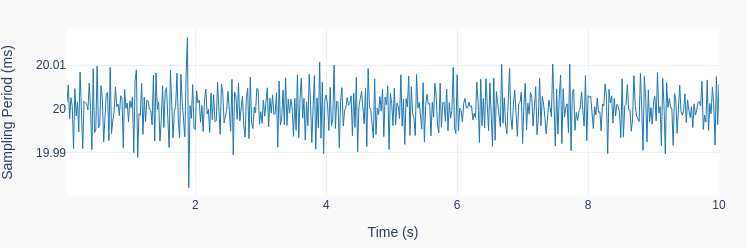

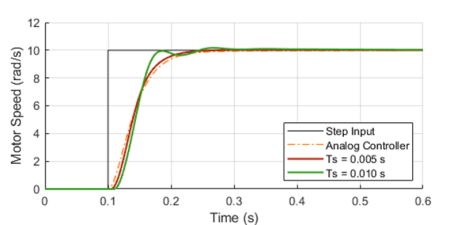

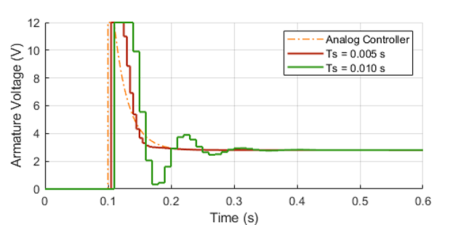

The graphs below show the closed-loop response of the analog plant (DC motor) as well as the corresponding output of the discrete controller for a sampling period of 0.01 and 0.005 seconds. The equivalent analog controller using the same PID gains is also shown as a reference. Although not on the graphs, the discrete PID with a sampling period of 0.001 seconds produces virtually the same response as the continuous one.

As it can be seen in the graphs, the lower sampling period caused the plant output to oscillate. Further increasing![]() would increase the amplitude of the oscillations, eventually making the system unstable. This well known behavior is caused by the discretization of the controller, where the plant basically behaves in an open loop fashion in between sample points. Even though this problem can be approached mathematically, tackling it using a simulation tool can provide valuable insight on the compromises between sampling period and PID gains, during the initial design of the controller.

would increase the amplitude of the oscillations, eventually making the system unstable. This well known behavior is caused by the discretization of the controller, where the plant basically behaves in an open loop fashion in between sample points. Even though this problem can be approached mathematically, tackling it using a simulation tool can provide valuable insight on the compromises between sampling period and PID gains, during the initial design of the controller.

Before we put our digital PID into a Python class, let’s go over a few features that can make the controller more robust for practical applications.

Saturation and Anti-Windup

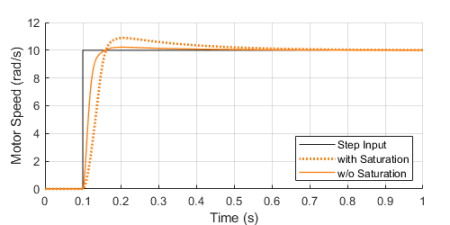

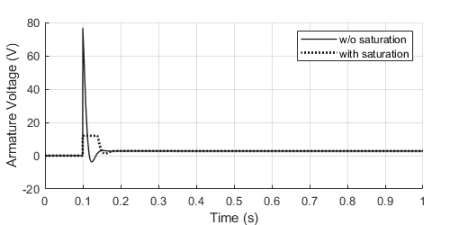

If we were to use some very aggressive gains for our motor PID controller, the step response could be further improved as shown with the solid trace below. You’ll also notice an unpractical armature voltage spike over 60 V! In reality, the controller output will saturate at its maximum (or minimum) output capability, in our case 12 V, producing the dotted line traces instead.

Once the controller output is saturated, the integral term compensation keeps increasing in an attempt to reduce the accumulated error. By the time the controller “comes back” from the saturation state, the integral term is “wound-up”, resulting in an overshoot of the response, as it can be seen by contrasting the dotted and solid orange lines above.

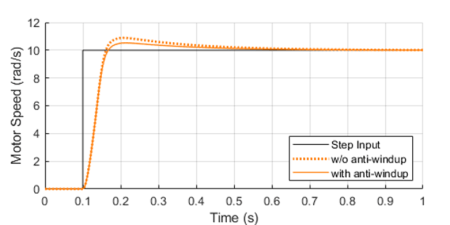

By implementing anti-windup logic in the discrete controller, the overshoot caused by potential saturation can be reduced, as shown on the left.

The basic idea is to turn off the integral term of the PID (as we’ll see in the Python class at the end) every time an upper or lower saturation limit is exceeded. This is a common improvement used in digital PID controllers.

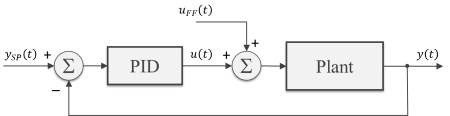

Feed-Forward and Derivative Term Filtering

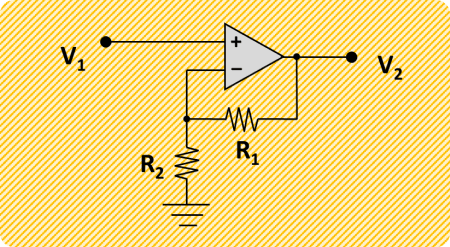

Another useful improvement that can be made to our digital PID is to allow for a feed-forward signal![]() in its implementation. The feed-forward term reduces the contribution of the controller output signal

in its implementation. The feed-forward term reduces the contribution of the controller output signal ![]() , making the system less susceptible to noise in the measurement of the plant output used to calculate the error

, making the system less susceptible to noise in the measurement of the plant output used to calculate the error![]() .

.

While not always possible, in some special situations, we can pre-calculate the feed-forward signal as a function of time and add it to controller output as shown in the block diagram. Typical applications involve a known “control path” such as a robotic manipulator (with pre-programmed motion paths) or a vehicle’s cruise control (on a highway with known topology).

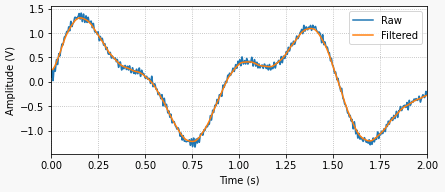

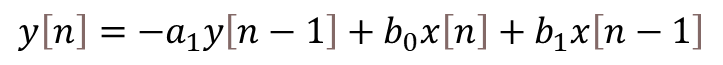

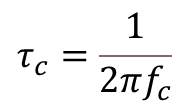

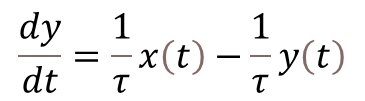

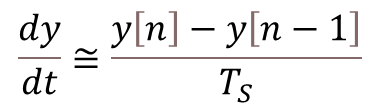

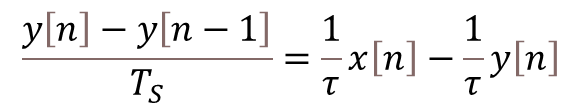

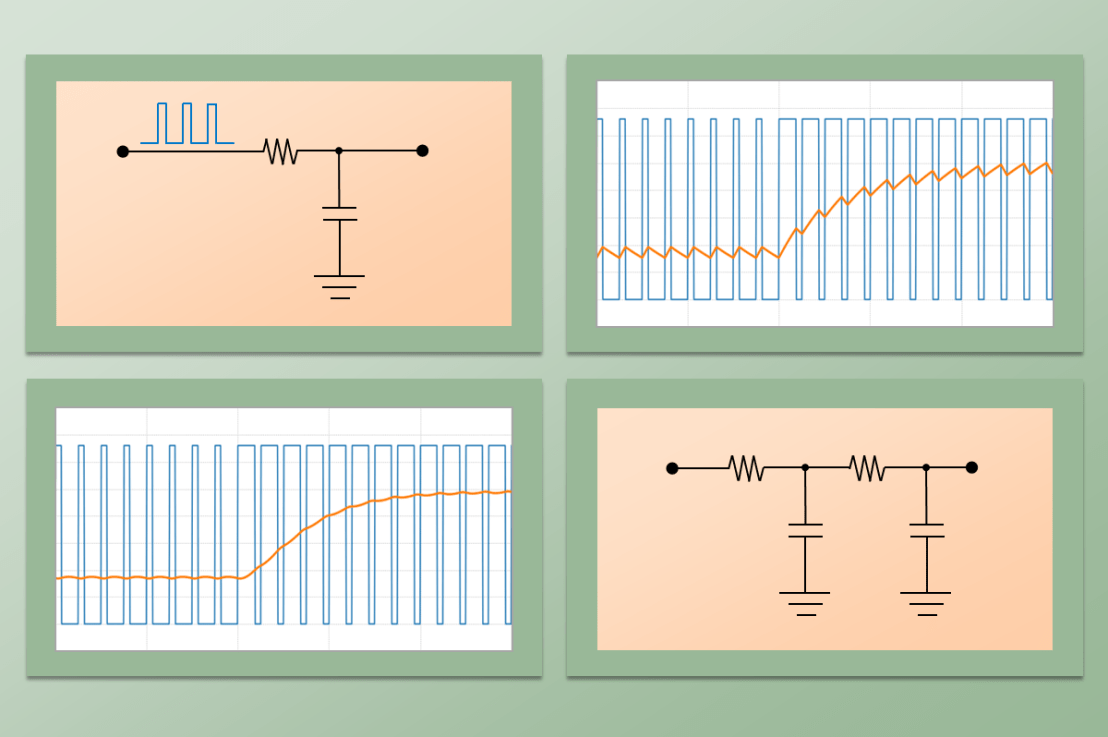

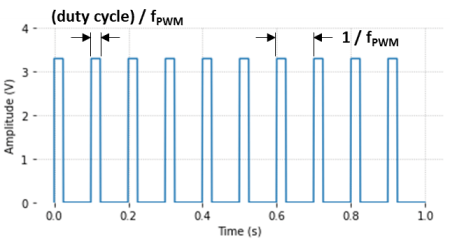

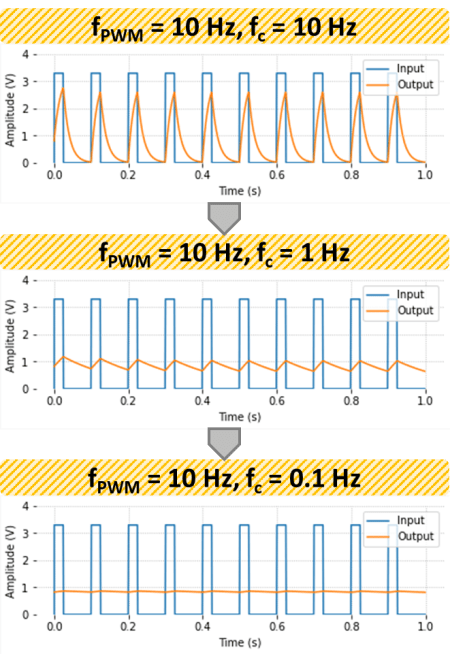

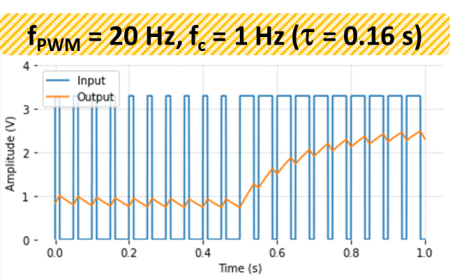

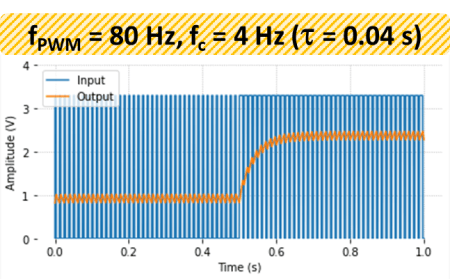

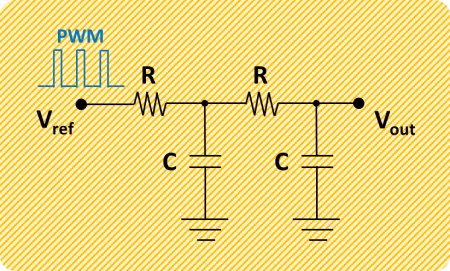

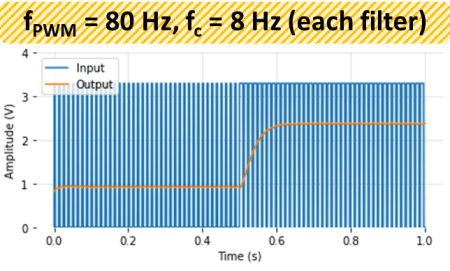

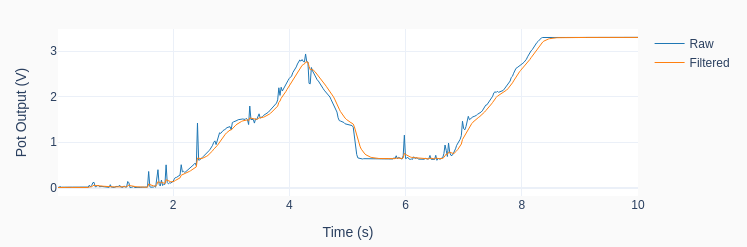

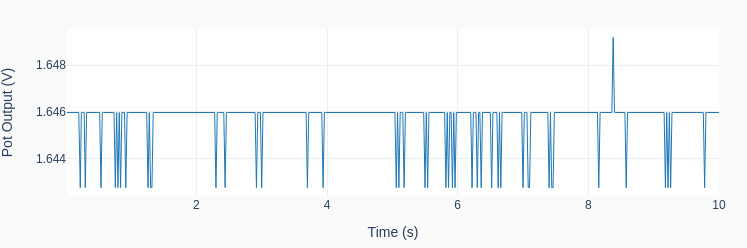

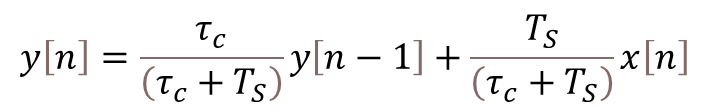

As I mentioned earlier in this post, the derivative term of the PID is quite sensitive to noise in the calculated error signal![]() , which primarily comes from the transducers used to measure the plant output. One way to help mitigate this effect is the addition of a low-pass filter to the output of the derivative term inside the controller. Let’s use my favorite first-order digital filter, given by the difference equation below, where

, which primarily comes from the transducers used to measure the plant output. One way to help mitigate this effect is the addition of a low-pass filter to the output of the derivative term inside the controller. Let’s use my favorite first-order digital filter, given by the difference equation below, where![]() is the derivative term output and

is the derivative term output and![]() is the corresponding filtered output signal.

is the corresponding filtered output signal.

PID Python Class

Finally, it’s time to put it all together inside a Python class. If you go through the code below, you’ll be able to identify all the components that were discussed in the previous three sections. The PID class should be instantiated before entering the execution loop, while the control method is called every time step inside the execution loop. In my next post we will use this class to control the speed of a small DC motor.

class PID:

def __init__(self, Ts, kp, ki, kd, umax=1, umin=-1, tau=0):

#

self._Ts = Ts # Sampling period (s)

self._kp = kp # Proportional gain

self._ki = ki # Integral gain

self._kd = kd # Derivative gain

self._umax = umax # Upper output saturation limit

self._umin = umin # Lower output saturation limit

self._tau = tau # Derivative term filter time constant (s)

#

self._eprev = [0, 0] # Previous errors e[n-1], e[n-2]

self._uprev = 0 # Previous controller output u[n-1]

self._udfiltprev = 0 # Previous derivative term filtered value

def control(self, ysp, y, uff=0):

#

# Calculating error e[n]

e = ysp - y

# Calculating proportional term

up = self._kp * (e - self._eprev[0])

# Calculating integral term (with anti-windup)

ui = self._ki*self._Ts * e

if (self._uprev+uff >= self._umax) or (self._uprev+uff <= self._umin):

ui = 0

# Calculating derivative term

ud = self._kd/self._Ts * (e - 2*self._eprev[0] + self._eprev[1])

# Filtering derivative term

udfilt = (

self._tau/(self._tau+self._Ts)*self._udfiltprev +

self._Ts/(self._tau+self._Ts)*ud

)

# Calculating PID controller output u[n]

u = self._uprev + up + ui + udfilt + uff

# Updating previous time step errors e[n-1], e[n-2]

self._eprev[1] = self._eprev[0]

self._eprev[0] = e

# Updating previous time step output value u[n-1]

self._uprev = u - uff

# Updating previous time step derivative term filtered value

self._udfiltprev = udfilt

# Limiting output (just to be safe)

if u < self._umin:

u = self._umin

elif u > self._umax:

u = self._umax

# Returning controller output at current time step

return u