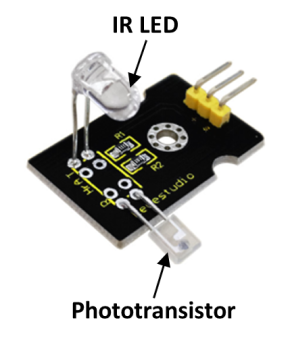

Pulse rate can be detected using a variety of physical principles. One way of doing it is by applying infrared light to one side of the tip of your finger and sensing the “output” on the other side with a phototransistor. The blood flow through the capillaries at the finger tip fluctuates with the same frequency (rate) of your pulse. That fluctuation can be detected after processing the signal captured by the sensor.

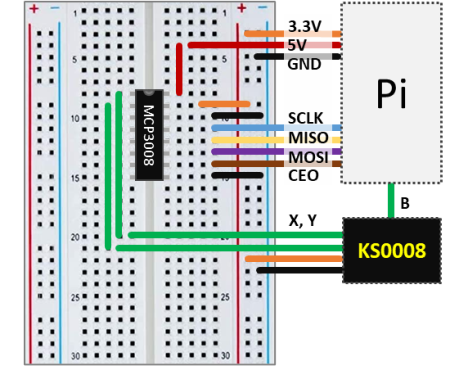

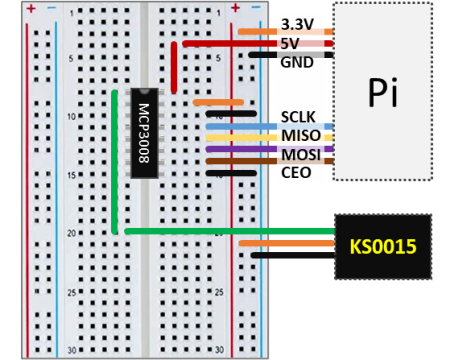

Keyestudio has a rudimentary pulse rate monitor (KS0015) that does the trick. In this post we will go over the signal processing and how to display the pulse rate in real time. Since the KS0015 outputs an analog signal, it has to be used with the MCP3008 analog-to-digital converter chip, as illustrated in the schematics below.

As noted in previous posts, adopting a reference voltage of 3.3V for the MCP3008 provides the best resolution for the analog-to-digital conversion. The sensor output therefore has to be no greater than 3.3V, which can be achieved by using 3.3 instead of 5V as the supply voltage for the KS0015.

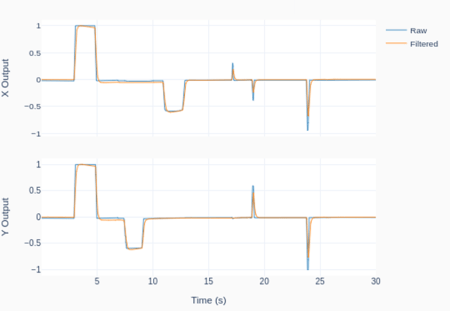

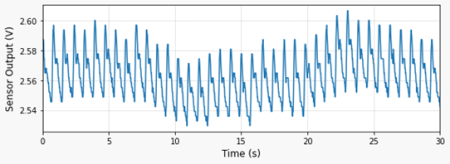

The very first thing to do is to look at the signal coming from the sensor as the tip of my index finger is placed between the IR LED and the phototransistor. The plot on the left can be generated by running the Python code below.

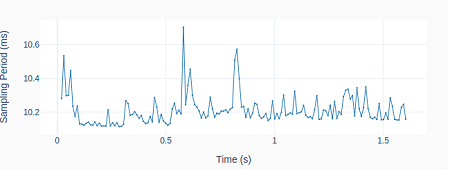

By inspecting the program, the first thing to observe is the sampling period (tsample) of 0.02 s. Since we don’t know much about the signal, it’s always good to start with a smaller value. The second thing is the wait time of 5 seconds before collecting any data. After tinkering around for a bit, I realized that the sensor is very sensitive to finger movements. Therefore, waiting for the signal to “settle down” really helps.

# Importing modules and classes

import time

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from gpiozero import MCP3008

# Defining function for plotting

def make_fig():

# Creating Matplotlib figure

fig = plt.figure(

figsize=(8, 3),

facecolor='#f8f8f8',

tight_layout=True)

# Adding and configuring axes

ax = fig.add_subplot(xlim=(0, max(t)))

ax.set_xlabel('Time (s)', fontsize=12)

ax.grid(linestyle=':')

# Returning axes handle

return ax

# Creating object for the pulse rate sensor output

vch = MCP3008(channel=0, clock_pin=11, mosi_pin=10, miso_pin=9, select_pin=8)

# Assigning some parameters

tsample = 0.02 # Sampling period for code execution (s)

tstop = 30 # Total execution time (s)

vref = 3.3 # Reference voltage for MCP3008

# Preallocating output arrays for plotting

t = [] # Time (s)

v = [] # Sensor output voltage (V)

# Waiting for 5 seconds for signal stabilization

time.sleep(5)

# Initializing variables and starting main clock

tprev = 0

tcurr = 0

tstart = time.perf_counter()

# Running execution loop

print('Running code for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Getting current time (s)

tcurr = time.perf_counter() - tstart

# Doing I/O and computations every `tsample` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tsample) - np.floor(tprev/tsample)) == 1:

# Getting current sensor voltage

valuecurr = vref * vch.value

# Assigning current values to output arrays

t.append(tcurr)

v.append(valuecurr)

# Updating previous time value

tprev = tcurr

print('Done.')

# Releasing GPIO pins

vch.close()

# Plotting results

ax = make_fig()

ax.set_ylabel('Sensor Output (V)', fontsize=12)

ax.plot(t, v, linewidth=1.5, color='#1f77b4')

ax = make_fig()

ax.set_ylabel('Sampling Period (ms)', fontsize=12)

ax.plot(t[1::], 1000*np.diff(t), linewidth=1.5, color='#1f77b4')

Digital Filtering and Pulse Detection

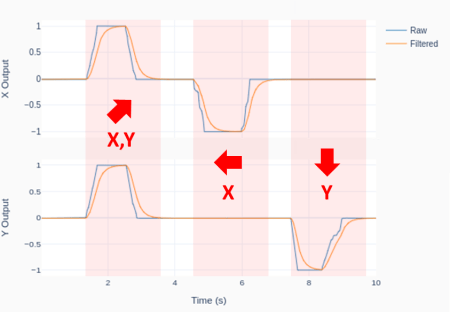

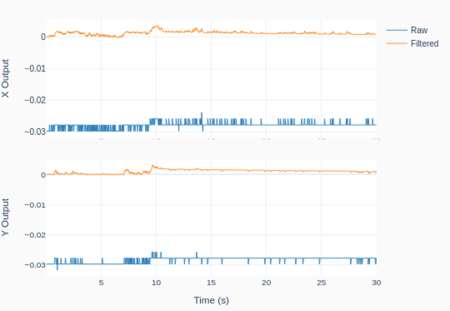

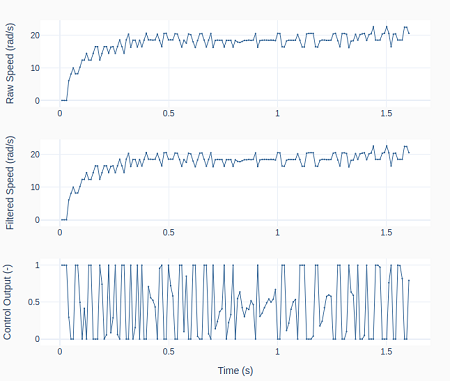

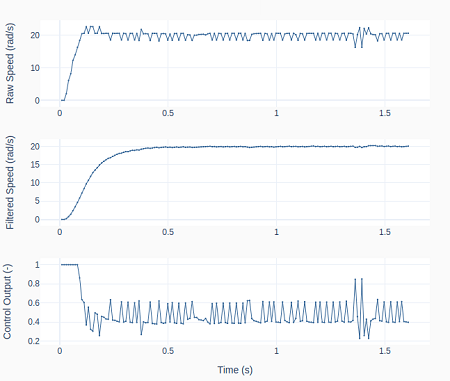

In this stage of the signal processing, let’s put some of the content of previous posts to good use. More specifically digital band-pass filtering and event detection for the pulse signal.

First let’s remove the low and high frequency components of the signal that are outside the band of interest. I chose 0.5 and 5 Hz (30 and 300 beats per minute) as the cutoff frequencies. That seems to be a reasonable bandwidth to account for the filter attenuation at the cutoff frequencies, as well as for the human heart “range of operation”.

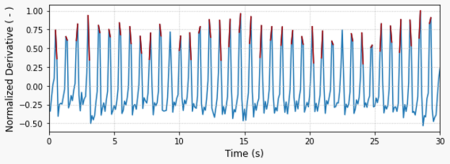

Then, let’s calculate the derivative of the signal so it’s easier to detect the pulse events. By normalizing the derivative based on its maximum value, the signal amplitude becomes more consistent and therefore a single value threshold can be used. In this case 25% of the maximum value.

The plot on the top shows the normalized derivative of the filtered signal. In red are the trigger events detected by the function find_cluster, which I placed inside the module utils.py . As usual, all the code for this post can be found on my GitHub page.

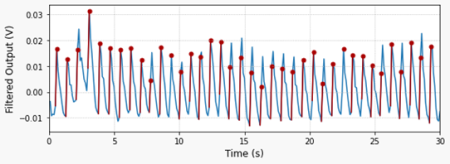

The plot on the bottom shows the identified trigger events (red dots) displayed on the filtered sensor output signal.

The Python program below is an extension of the one in the previous section, where the digital filter and the trigger detection features are now incorporated. The pulse rate is calculated using the median of the time difference between two consecutive trigger events. In this case, using the median instead of the mean is recommended since it makes the calculation more robust to outliers.

Running the code will generate the two graphs shown above and print the median pulse rate for the corresponding (30-second) data acquisition window. You will notice that the signal amplitude is fairly small (approx. 30 mV) and very sensitive to the finger tip location. It might take a few tries to find the correct position and pressure for the finger.

# Importing modules and classes

import time

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from gpiozero import MCP3008

from utils import find_cluster

# Defining function for plotting

def make_fig():

# Creating Matplotlib figure

fig = plt.figure(

figsize=(8, 3),

facecolor='#f8f8f8',

tight_layout=True)

# Adding and configuring axes

ax = fig.add_subplot(xlim=(0, max(t)))

ax.set_xlabel('Time (s)', fontsize=12)

ax.grid(linestyle=':')

# Returning axes handle

return ax

# Creating object for the pulse rate sensor output

vch = MCP3008(channel=0, clock_pin=11, mosi_pin=10, miso_pin=9, select_pin=8)

# Assigning some parameters

tsample = 0.1 # Sampling period for code execution (s)

tstop = 30 # Total execution time (s)

vref = 3.3 # Reference voltage for MCP3008

# Preallocating output arrays for plotting

t = np.array([]) # Time (s)

v = np.array([]) # Sensor output voltage (V)

vfilt = np.array([]) # Filtered sensor output voltage (V)

# Waiting for 5 seconds for signal stabilization

time.sleep(5)

# First order digital band-pass filter parameters

fc = np.array([0.5, 5]) # Filter cutoff frequencies (Hz)

tau = 1/(2*np.pi*fc) # Filter time constants (s)

# Filter difference equation coefficients

a0 = tau[0]*tau[1]+(tau[0]+tau[1])*tsample+tsample**2

a1 = -(2*tau[0]*tau[1]+(tau[0]+tau[1])*tsample)

a2 = tau[0]*tau[1]

b0 = tau[0]*tsample

b1 = -tau[0]*tsample

# Assigning normalized coefficients

a = np.array([1, a1/a0, a2/a0])

b = np.array([b0/a0, b1/a0])

# Initializing filter values

x = [vref*vch.value] * len(b) # x[n], x[n-1]

y = [0] * len(a) # y[n], y[n-1], y[n-2]

time.sleep(tsample)

# Initializing variables and starting main clock

tprev = 0

tcurr = 0

tstart = time.perf_counter()

# Running execution loop

print('Running code for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Getting current time (s)

tcurr = time.perf_counter() - tstart

# Doing I/O and computations every `tsample` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tsample) - np.floor(tprev/tsample)) == 1:

# Getting current sensor voltage

valuecurr = vref * vch.value

# Assigning sensor voltage output to input signal array

x[0] = valuecurr

# Filtering signals

y[0] = -np.sum(a[1::]*y[1::]) + np.sum(b*x)

# Updating output arrays

t = np.concatenate((t, [tcurr]))

v = np.concatenate((v, [x[0]]))

vfilt = np.concatenate((vfilt, [y[0]]))

# Updating previous filter output values

for i in range(len(a)-1, 0, -1):

y[i] = y[i-1]

# Updating previous filter input values

for i in range(len(b)-1, 0, -1):

x[i] = x[i-1]

# Updating previous time value

tprev = tcurr

print('Done.')

# Releasing pins

vch.close()

# Calculating and normalizing sensor signal derivative

dvdt = np.gradient(vfilt, t)

dvdt = dvdt/np.max(dvdt)

# Finding heart rate trigger event times

icl, ncl = find_cluster(dvdt>0.25, 1)

ttrigger = t[icl]

# Calculating heart rate (bpm)

bpm = 60/np.median(np.diff(ttrigger))

print("Heart rate = {:0.0f} bpm".format(bpm))

# Plotting results

ax = make_fig()

ax.set_ylabel('Normalized Derivative ( - )', fontsize=12)

ax.plot(t, dvdt, linewidth=1.5, color='#1f77b4', zorder=0)

for ik, nk in zip(icl, ncl):

if ik+nk < len(t):

ax.plot(t[ik:ik+nk], dvdt[ik:ik+nk], color='#aa0000')

ax = make_fig()

ax.set_ylabel('Filtered Output (V)', fontsize=12)

ax.plot(t, vfilt, linewidth=1.5, color='#1f77b4', zorder=0)

for ik, nk in zip(icl, ncl):

ax.plot(t[ik:ik+nk], vfilt[ik:ik+nk], color='#aa0000')

ax.scatter(t[ik+1], vfilt[ik+1], s=25, c='#aa0000')

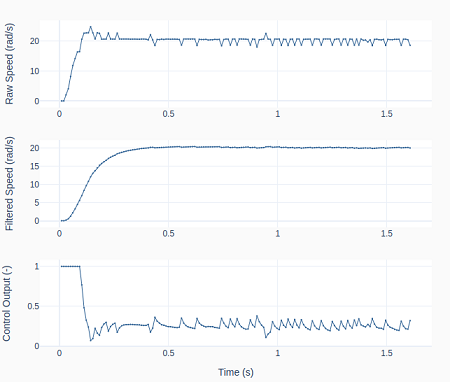

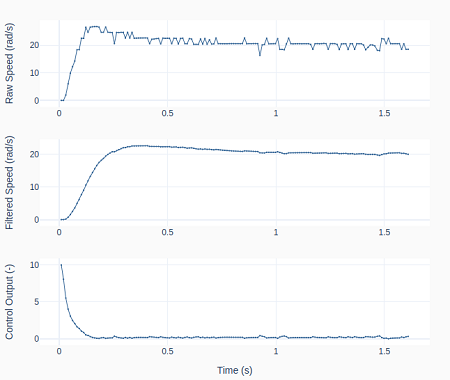

Real-time Pulse Rate Detection

Now that we have the pulse rate detection and calculation working, we can modify the code from the previous section to add the real-time display of the pulse rate. For this step, we will use a 7-segment LED display with a TM1637 chip. In case you don’t have one, all the calls for the tm object in the code below should be removed and a simple

print("Heart rate = {:0.0f} bpm".format(bpm))

can be used to replace the code line

tm.number(int(bpm))

Also, notice how we are using a circular buffer (tbuffer) of 20 seconds that holds the signal for the pulse rate calculation. The buffer is updated every tsample seconds and the actual pulse rate calculation occurs every tdisp seconds. Through comparison with the previous program, you can see how the bpm calculation is now placed inside the execution loop, hence happening in real-time.

# Importing modules and classes

import time

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import tm1637

from gpiozero import MCP3008

from utils import find_cluster

# Defining function for plotting

def make_fig():

# Creating Matplotlib figure

fig = plt.figure(

figsize=(8, 3),

facecolor='#f8f8f8',

tight_layout=True)

# Adding and configuring axes

ax = fig.add_subplot(xlim=(0, max(t)))

ax.set_xlabel('Time (s)', fontsize=12)

ax.grid(linestyle=':')

# Returning axes handle

return ax

# Creating object for the pulse rate sensor output and LED display

vch = MCP3008(channel=0, clock_pin=11, mosi_pin=10, miso_pin=9, select_pin=8)

tm = tm1637.TM1637(clk=18, dio=17)

# Assigning some parameters

tsample = 0.1 # Sampling period for code execution (s)

tstop = 60 # Total execution time (s)

tbuffer = 20 # Data buffer length(s)

tdisp = 1 # Display update period (s)

vref = 3.3 # Reference voltage for MCP3008

# Preallocating circular buffer arrays for real-time processing

t = np.array([]) # Time (s)

v = np.array([]) # Sensor output voltage (V)

vfilt = np.array([]) # Filtered sensor output voltage (V)

# Waiting for 5 seconds for signal stabilization

time.sleep(5)

# First order digital band-pass filter parameters

fc = np.array([0.5, 5]) # Filter cutoff frequencies (Hz)

tau = 1/(2*np.pi*fc) # Filter time constants (s)

# Filter difference equation coefficients

a0 = tau[0]*tau[1]+(tau[0]+tau[1])*tsample+tsample**2

a1 = -(2*tau[0]*tau[1]+(tau[0]+tau[1])*tsample)

a2 = tau[0]*tau[1]

b0 = tau[0]*tsample

b1 = -tau[0]*tsample

# Assigning normalized coefficients

a = np.array([1, a1/a0, a2/a0])

b = np.array([b0/a0, b1/a0])

# Initializing filter values

x = [vref*vch.value] * len(b) # x[n], x[n-1]

y = [0] * len(a) # y[n], y[n-1], y[n-2]

time.sleep(tsample)

# Initializing variables and starting main clock

tprev = 0

tcurr = 0

tstart = time.perf_counter()

# Running execution loop

tm.show('Hold')

print('Running code for', tstop, 'seconds ...')

print('Waiting', tbuffer, 'seconds for buffer fill.')

while tcurr <= tstop:

# Getting current time (s)

tcurr = time.perf_counter() - tstart

# Doing I/O and computations every `tsample` seconds

if (np.floor(tcurr/tsample) - np.floor(tprev/tsample)) == 1:

# Getting current sensor voltage

valuecurr = vref * vch.value

# Assigning sensor voltage output to input signal array

x[0] = valuecurr

# Filtering signals

y[0] = -np.sum(a[1::]*y[1::]) + np.sum(b*x)

# Updating circular buffer arrays

if len(t) == tbuffer/tsample:

t = t[1::]

v = v[1::]

vfilt = vfilt[1::]

t = np.concatenate((t, [tcurr]))

v = np.concatenate((v, [x[0]]))

vfilt = np.concatenate((vfilt, [y[0]]))

# Updating previous filter output values

for i in range(len(a)-1, 0, -1):

y[i] = y[i-1]

# Updating previous filter input values

for i in range(len(b)-1, 0, -1):

x[i] = x[i-1]

# Processing signal in the buffer every `tdisp` seconds

if ((np.floor(tcurr/tdisp) - np.floor(tprev/tdisp)) == 1) & (tcurr > tbuffer):

# Calculating and normalizing sensor signal derivative

dvdt = np.gradient(vfilt, t)

dvdt = dvdt/np.max(dvdt)

# Finding heart rate trigger event times

icl, ncl = find_cluster(dvdt>0.25, 1)

ttrigger = t[icl]

# Calculating and displaying pulse rate (bpm)

bpm = 60/np.median(np.diff(ttrigger))

tm.number(int(bpm))

# Updating previous time value

tprev = tcurr

print('Done.')

tm.show('Done')

# Releasing pins

vch.close()