These types of LED displays are quite popular and can be used to add a visual output to a Raspberry Pi automation project. In this post, I will be talking about the KS0445 4-digit LED Display Module from keyestudio. While keyestudio kits are primarily designed to work with Arduino, they are perfectly suitable for Pi applications.

In theory, any LED 4-digit Display using a TM1637 chip can be used with the Python code that will be shown.

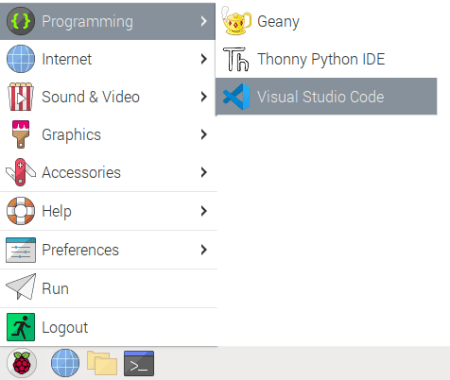

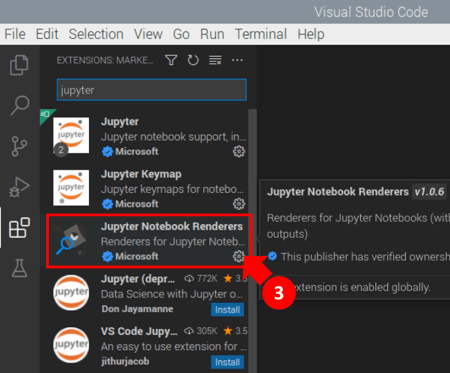

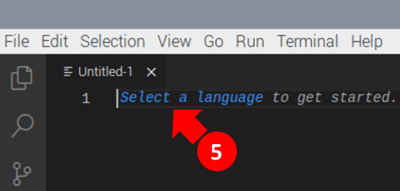

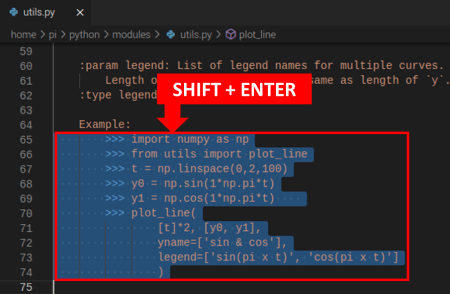

The first step is to install the TM1637 Python package containing the class that will simplify controlling the LED display quite a bit. As a side note, I strongly encourage installing VS Code on the Pi, so you can code like a pro.

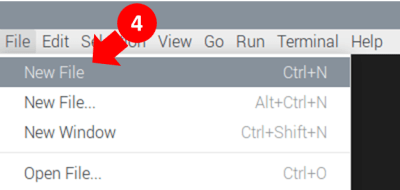

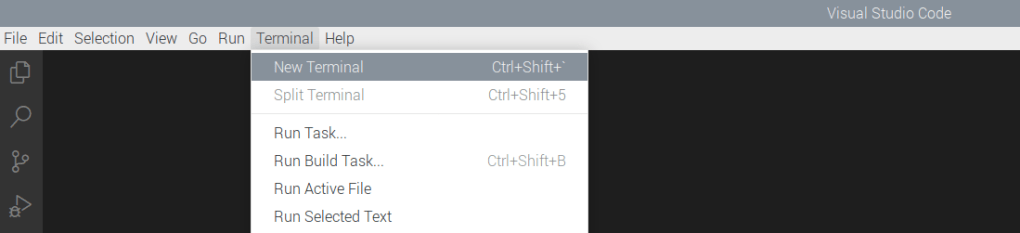

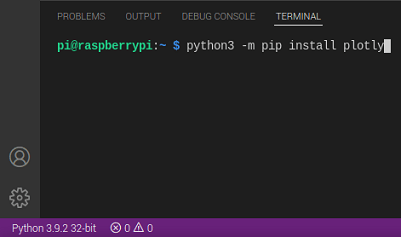

Open a terminal window in VS Code and type:

pip install raspberrypi-tm1637

Once the installation is complete, you can wire the display as shown below and try the Python code that follows. It illustrates how straightforward it is to use some of the methods of the TM1637 class that come in the package.

# Importing modules and classes

import tm1637

import time

import numpy as np

from datetime import datetime

from gpiozero import CPUTemperature

# Creating 4-digit 7-segment display object

tm = tm1637.TM1637(clk=18, dio=17) # Using GPIO pins 18 and 17

clear = [0, 0, 0, 0] # Defining values used to clear the display

# Displaying a rolling string

tm.write(clear)

time.sleep(1)

s = 'This is pretty cool'

tm.scroll(s, delay=250)

time.sleep(2)

# Displaying CPU temperautre

tm.write(clear)

time.sleep(1)

cpu = CPUTemperature()

tm.temperature(int(np.round(cpu.temperature)))

time.sleep(2)

# Displaying current time

tm.write(clear)

time.sleep(1)

now = datetime.now()

hh = int(datetime.strftime(now,'%H'))

mm = int(datetime.strftime(now,'%M'))

tm.numbers(hh, mm, colon=True)

time.sleep(2)

tm.write(clear)

Raspberry Pi Stopwatch with LED Display

That was pretty much it for the LED display. However, let’s go for an Easter egg, where we implement a stopwatch that can be controlled by keyboard inputs. The main feature here is the use of the Python pynput package, which seamlessly enables non-blocking keyboard inputs. To get started, in a terminal window in VS Code, type:

pip install pynput

To make things more interesting, I created the class StopWatch with the following highlights:

- First and foremost, could the entire code be written using a function (or a few functions) or even as a simple script? Yes, it could. However, using a class makes for code that is much more modular and expandable, and that can easily be integrated into other code.

- At the center of the the StopWatch class is the execution loop method. For conciseness and readability, all other methods (with very descriptive names) are called from within this execution loop.

- The beauty of using a class and therefore its methods is that the latter can be called from different points in the code, as it is the case of the

start_watch()method, for example. - Finally, as the code is written as a class vs. functions, all the variables can be defined as class attributes. That really reduces complexity with input arguments, if functions were to be used instead.

# Importing modules and classes

import time

import tm1637

import numpy as np

from pynput import keyboard

class StopWatch:

"""

The class to represent a digital stopwatch.

**StopWatch** runs on a Raspberry PI and uses a 4-digit 7-segment display

with a TM1637 control chip.

The following keyboard keys are used:

* ``'s'`` to start/stop the timer.

* ``'r'`` to reset the timer.

* ``'q'`` to quit the application.

"""

def __init__(self):

"""

Class constructor.

"""

# Creating 4-digit 7-segment display object

self.tm = tm1637.TM1637(clk=18, dio=17) # Using GPIO pins 18 and 17

self.tm.show('00 0') # Initializing stopwatch display

# Creating keyboard event listener object

self.myevent = keyboard.Events()

self.myevent.start()

# Defining time control variables (in seconds)

self.treset = 60 # Time at which timer resets

self.ts = 0.02 # Execution loop time step

self.tdisp = 0.1 # Display update period

self.tstart = 0 # Start time

self.tstop = 0 # Stop time

self.tcurr = 0 # Current time

self.tprev = 0 # Previous time

# Defining execution flow control flags

self.run = False # Timer run flag

self.quit = False # Application quit flag

# Running execution loop

self.runExecutionLoop()

def runExecutionLoop(self):

"""

Run the execution loop for the stopwatch.

"""

# Running until quit request is received

while not self.quit:

# Pausing to make CPU life easier

time.sleep(self.ts)

# Updating current time value

self.update_time()

# Handling keyboard events

self.handle_event()

# Checking if automatic reset time was reached

if self.tcurr >= self.treset:

self.stop_watch()

self.reset_watch()

self.start_watch()

# Updating digital display

self.update_display()

# Stroing previous time step

self.tprev = self.tcurr

def handle_event(self):

"""

Handle non-blocking keyboard inputs that control stopwatch.

"""

# Getting keyboard event

event = self.myevent.get(0.0)

if event is not None:

# Checking for timer start/stop

if event.key == keyboard.KeyCode.from_char('s'):

if type(event) == keyboard.Events.Release:

if not self.run:

self.run = True

self.start_watch()

elif self.run:

self.run = False

self.stop_watch()

# Checking for timer reset

elif event.key == keyboard.KeyCode.from_char('r'):

if type(event) == keyboard.Events.Release:

if not self.run:

self.reset_watch()

elif self.run:

print('Stop watch before resetting.')

# Checking for application quit

elif event.key == keyboard.KeyCode.from_char('q'):

self.quit = True

self.tm.write([0, 0, 0, 0])

print('Good bye.')

def start_watch(self):

""" Update start time. """

self.tstart = time.perf_counter()

def stop_watch(self):

""" Update stop time. """

self.tstop = self.tcurr

def reset_watch(self):

""" Reset timer. """

self.tstop = 0

self.tm.show('00 0')

def update_time(self):

""" Update timer value. """

if self.run:

self.tcurr = time.perf_counter() - self.tstart + self.tstop

def update_display(self):

""" Update digital display every 'tdisp' seconds. """

if (np.floor(self.tcurr/self.tdisp) - np.floor(self.tprev/self.tdisp)) == 1:

# Creating timer display string parts (seconds, tenths of a second)

if int(self.tcurr) < 10:

tsec = '0' + str(int(self.tcurr))

else:

tsec = str(int(self.tcurr))

ttenth = str(int(np.round(10*(self.tcurr-int(self.tcurr)))))

# Showing string on digital display

self.tm.show(tsec + ' ' + ttenth)

# Running instance of StopWatch class

if __name__ == "__main__":

StopWatch()